David Sylvian: gloomy songs about being happy - an appreciation

Late one recent Tuesday night I sent a message to an old friend in Madrid.

“Did you know David Sylvian married Ingrid Chavez? I mean, in the 90s. But still.”

The catalyst for this was my latest obsession; not marriages of glamorous 80s pop idols to ghostwriters of Madonna songs, but the back catalogue of the former Japan frontman. I had been led down this sonic rabbithole during a period when I had a lot of writing work from home.

I work best to a soundtrack of minimalist music: a mix of drones, silences, spare piano, wispy synths. The kind of music that has spawned a million youtube playlists called “Music for Concentration” and has since been monetised by streaming services.

I listen to Max Richter’s eight-hour epic Sleep a lot, along with works by other artists such as Nils Frahm and Olafur Arnalds and I maintain a growing curated playlist for the purpose. I find vocals - or at least lyrics - are a distraction, so I was searching for the instrumental version of Forbidden Colours, the collaboration Sylvian made with Ryuichi Sakamoto for the Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence soundtrack in 1983.

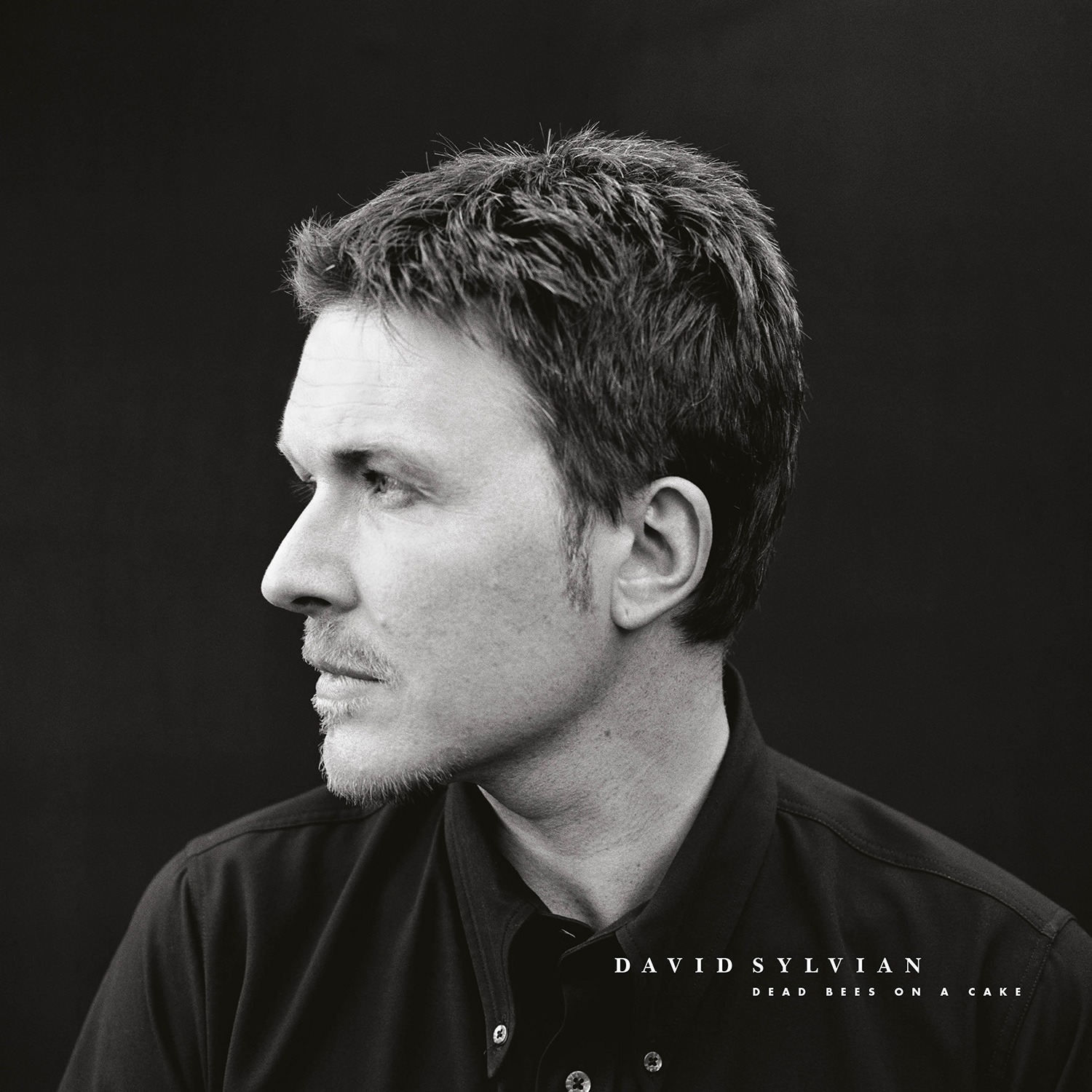

Instead, I stumbled over Thalheim, a remarkable track from Sylvian’s 1999 double album, Dead Bees on a Cake. This song is the audio equivalent of a waterhole in a deserted forest. The flange on the guitar is like a ripple on the surface of the water; the muted trumpet like a dragonfly hovering in the air. The languid beat gently cradles the listener as Sakamoto’s Fender Rhodes softly chimes. Sylvian sings of the shadows dissipating in the sunlight in his quiet baritone and raises the tension towards the end by changing the phrasing and the rhyme. The overall sound is reminiscent of Joni Mitchell’s earlier jazz-influenced outings on For the Roses and Court and Spark.

I was in love.

Other songs on the album, which featured more luminaries alongside Sakamoto, including Talvin Singh, Marc Ribot and Bill Frisell, had the same seductive vibe. What else had I been missing out on all these years?

A further investigation of his catalogue turned up some charming songs from 1988’s Secrets of the Beehive and Approaching Silence from 1999, a three-track album with a 30-minute instrumental song of the same name which is a must-have for those “music for exams” playlists. For half an hour ambient noise like the wind howling outside alternates with what sounds like a ship’s foghorn and other vague sonic artefacts.

I was in heaven.

What else?

Could it be time to go right back to Japan, the band that made him famous? The name made me flinch. I couldn’t help thinking of how they would be cancelled before they even began with a name like that now. Apparently it wasn’t meant to stick but they never got around to changing it.

Their early music is all over the place. They began in the mid-70s as a glam band, influenced by art rockers like Roxy Music. But one of my favourites of their early years is Life in Tokyo, a collaboration with electronic producer Giorgio Moroder, and another is the beautiful and minimalist Night Porter from 1980’s Gentlemen Take Polaroids. The latter gives a good indication of where the band, and Sylvian, were heading.

Chart success eluded them until they were on the verge of breaking up. Tin Drum, their final album together, before they later reformed as Rain Tree Crow, made the Top 20 in the UK and gave them a Top 5 single with the spare and moody Ghosts.

Sylvian had already collaborated with Sakamoto with Japan and as a solo artist, and they would work together many more times. He released almost 10 solo albums but became increasingly interested in collaboration and improvisation, and has released a dozen more with artists such as Sakamoto, Czukay, Robert Fripp and others.

As I sifted through his catalogue discovering new gems, I became obsessed with the idea that Sylvian had had what was to me at least, this secret career. A cache of work seemingly tailor-made for my own idiosyncratic tastes that had been completely unknown to me.

How could this have happened? Research was called for. A scan through a bio brought me the delicious titbit about his marriage to Ingrid Chavez, who co-wrote Madonna’s 1990 hit Justify My Love. Chavez is a poet and singer who lived in Minneapolis and briefly worked with Prince. She sang with Sylvian on a lovely song called Heartbeat, for Sakamoto’s 1992 album of the same name, and the pair were married two months after they met. They had two daughters together and divorced 12 years later. They appear to still be on good terms.

The pair lived in California for a while – a place that seems at odds with Sylvian’s wintry music and reclusive temperament – and at some point he apparently headed off to the New England woods to live on his own.

Sylvian seems drawn to solitude yet thrives on collaboration. Despite the fact that he composes most of his own work, much of his catalogue, with its sprawling canvas of genres, could not have been created without crucial contributions from others. First with members of Japan, Mick Karn in particular, and his inimitable fretless bass playing, and his own brother, Steve Jansen, on drums, who he has collaborated with throughout his life; then his long partnership with Sakamoto; the recordings with Holger Czukay, one of the most influential men in modern music, and many others.

What little I have gleaned about him has come from an apparently “official” website that hosts a few interviews - the top two being unattributed and undated. What does this mean? Has he written the questions and the long rambling answers? It’s most curious.

Like many artists who have been working for years he has a tidy and extremely dedicated fanbase eager for word of concert dates, new material and, apparently, coffee table books: Like Planets by Yuka Fujii is a photo essay documenting Sylvian’s transition from “glamorous pop star to retiring spiritual aspirant” (a reference to his exploration of Eastern religions). A promised tour in 2012 didn’t eventuate but he performed with a trio called the KIlowatt Hour in Norway a year later. Next week previously unreleased music by him will feature in a room at the Born Creative Festival in Tokyo.

I am still working my way through his catalogue. The latest discovery - the Czukay collaborations, two albums of two instrumental works each – are profoundly soothing. I will be sticking with them for a while before I investigate properly other works, which I have already noted have a more industrial edge, and see what else this singular creative force has in store.

Better late than never.